You know what time it is: October. Which means I’m making my way through a month’s worth of horror movies, Halloween episodes of my favorite TV shows, and a bunch of whatever kind of thing you’d consider It’s the Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown to be. I’m a big fan. I did not grow up enjoying horror or spooky things but have come to appreciate that they do not exist solely to peddle blood and gore but to tap into our collective fears, our values, and our psyche to tell us something about ourselves.

Last year for Halloween, I wrote a fairly hefty piece called Flesh & Blood that looked at the ways that nudity is used in horror films to emphasize different themes or tap into different fears. In that piece, I looked at how horror monsters punish young, naked, and sexually active youths with death, how old age is presented as a horror of its own, how nakedness may be used to alert our senses to danger, and how witches in horror often embrace nudity as a sign of power and strength, which may strike a fear of its own in our patriarchal society.

But then there’s Mary Harron’s American Psycho (2000), based on Bret Easton Ellis’s 1991 novel of the same name. Yes, there are young, nude women who die following sexual encounters, as is common in the death-by-sex horror trope, but that’s not the nudity that’s remarkable here. The female victims in American Psycho are not the “final girls” we’re used to rooting for from the start. They’re just some of the many victims in the film. What makes American Psycho unique is that the kills are not tied to some moral judgment about the victims, and the remarkable nudity is that of the killer. It’s used to convey the monster’s vanity rather than to disgust or frighten the viewer. It exposes our tendency to let wealthy, attractive, powerful men (with great business cards, mind you) get away with murder (figuratively and, in this case, literally… maybe?). It reveals a delicate masculinity desperate for power.

For these reasons, I think American Psycho deserves its own treatment, its own analysis of the way nudity is used to reinforce its themes and what the enduring message of the film is. So, here goes.

Making Patrick Bateman

There is an idea of a Patrick Bateman; some kind of abstraction. But there is no real me: only an entity, something illusory. And though I can hide my cold gaze, and you can shake my hand and feel flesh gripping yours and maybe you can even sense our lifestyles are probably comparable... I simply am not there.

-Christian Bale as Patrick Bateman, American Psycho (2000)

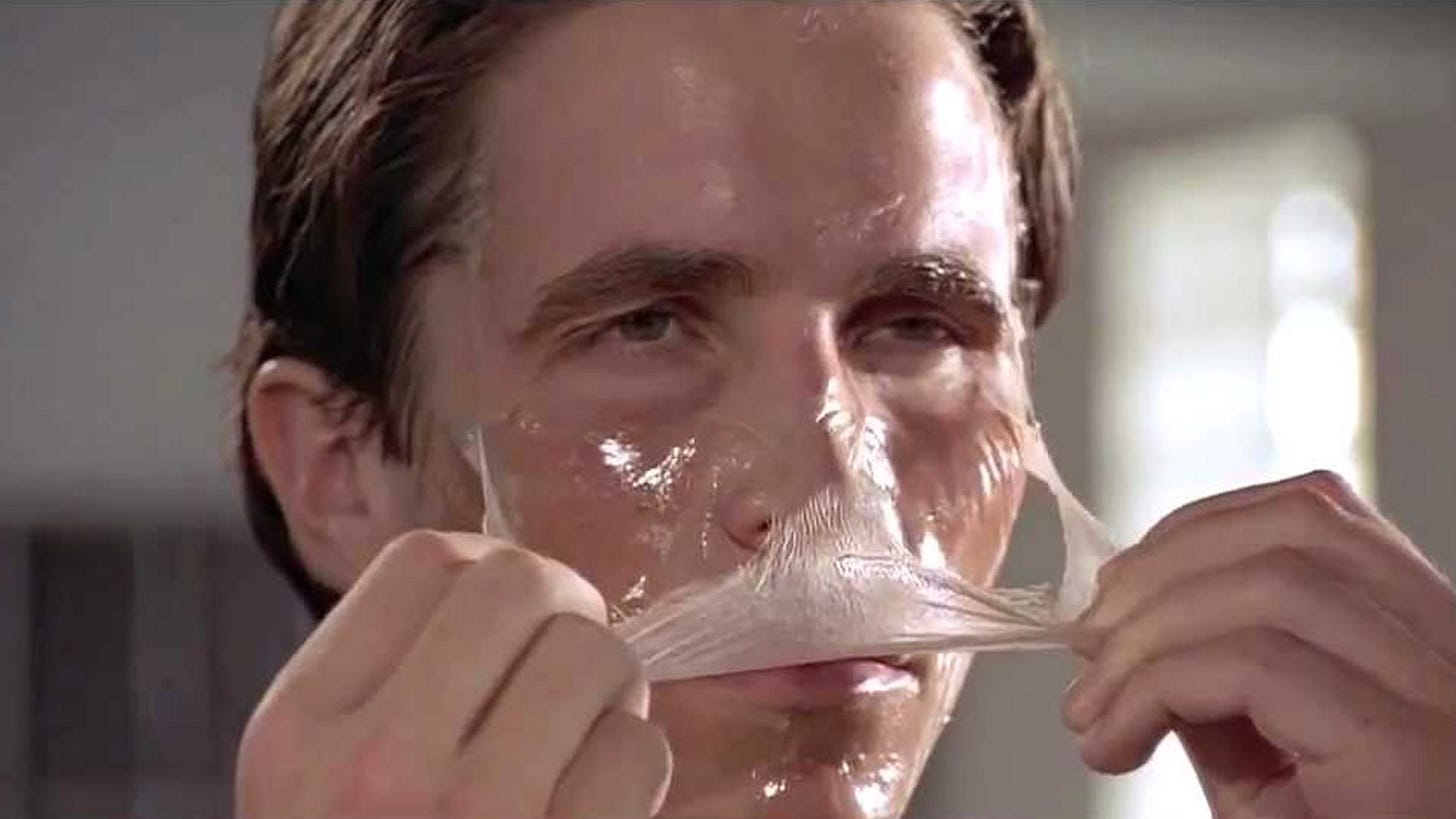

As the saying goes, “the clothes make the man,” and this is certainly true in the case of American Psycho’s main character, Patrick Bateman, who dons his bespoke pinstripe Valentino suit—selected from a walk-in closet of other bespoke suits—with pride and confidence. But the Valentino suit is just one piece in the “making” of Patrick Bateman. Rather, Bateman builds his identity through his physical body, in his almost grotesque but certainly comically exaggerated and obsessive attention to his physique, diet, hair, and skincare routine. The famous “morning routine” scene of the film feels like watching Frankenstein meticulously and methodically construct and animate his monster, piece by piece, limb by limb, until the final creation emerges. Bateman’s routine feels cold and robotic, but also hypnotic, as if we enter into the trance of becoming Bateman along with our narrator. Our narrator himself admits that he’s hardly human, as much as he may look and act it. Unlike Frankenstein’s monster, however, rather than the creature being curious and kind but repulsive and misunderstood, acting as a vehicle for a message about mankind’s cruelty, we get Bateman, an immaculately handsome yet wholly incurious and psychopathic monster, an avatar himself for the worst of humanity.

Bateman’s nakedness (or near-nakedness) during his morning skincare routine, his fitness regimen, and in the shower at various points during the film reminds us of his vanity but also seems to act as his grounding point, his cocoon, where he is his basest and most vulnerable self and where he reconstructs and recommits himself to his character before entering back into the world. But even at this basest point, we never get to Bateman’s truth. The custom suiting, the vocal affect, the meticulous attention to detail in business card fonts, and getting reservations at the right restaurants all build upon this character base, absolutely, and contribute to the making and maintenance of Patrick Bateman throughout the film. What is made clear, however, is that beneath the Valentino suits, beneath the perfect body, beneath the flawless skin, there really is no Patrick Bateman. All of it is a carefully crafted part of the character of Patrick Bateman, yes, but by our narrator’s own admission, he simply is not there. His humanity is simply missing.

Maintaining Patrick Bateman

I have all the characteristics of a human being: blood, flesh, skin, hair; but not a single, clear, identifiable emotion, except for greed and disgust. Something horrible is happening inside of me and I don't know why. My nightly bloodlust has overflown into my days. I feel lethal, on the verge of frenzy. I think my mask of sanity is about to slip.

-Christian Bale as Patrick Bateman, American Psycho (2000)

Unfortunately, keeping up a perfect physique, flawless skin, and getting reservations at Dorsia are not enough to maintain Patrick Bateman—not enough to give him the upper hand compared to the sea of interchangeable Paul Allens, Timothy Bryces, and Craig McDermotts. Maintaining Patrick Bateman requires competition, a competition satirized by the film’s business card comparison scene, wherein the all-male group of investment bankers reveals their nearly identical business cards one by one while we listen to our narrator scrutinize the fine details of each and watch Bateman agonize on screen over their perceived superiority. This anxiety heightens over the course of the film as we watch Bateman’s mask slip and his psychopathy bleed through to the surface. The maintenance of Patrick Bateman hinges on his pursuit of alpha male status at all costs: beating out his male competition, punishing those men who don’t compete at all, and subjugating (read: torturing and murdering) women left and right. It is in these cases that we see dress and undress come back into play. Bateman is not always nude when he kills, and he doesn’t always kill when he’s nude, but Bateman’s state of dress is an important part of his character, especially when he is killing.

Early in the film, having perceived his coworker Paul Allen as his prime competition (because of his amazing business card and superior apartment), Bateman decides to murder him. In this case, Bateman remains fully clothed while he gets him drunk and then axes him to death, not letting slip any part of the persona he has built for himself. Unlike later murders, he wears a clear plastic raincoat over his suit, an additional barrier between himself and his victims—but also between himself and accountability. Vulnerability is not something Bateman can afford around his male competition—not in the office and certainly not in his home. Everything about the mess associated with the murder of Paul Allen is accounted for, cleaned up, swept under the rug, and ignored by those watching him drag a body bag out of his building.

Conversely, we see Bateman drop the outer layers and remain nude only when he is alone, focusing on his own vanity, primping, and preening—or admiring himself in the mirror while having sex with prostitutes. It’s in the presence of his female victims that Bateman drops the artifice of the Valentino suit. During his sexual encounters, of course, he strips the external pretenses, even if he holds onto some of his affect. Eventually, he gives in to his psychotic impulses, lets his mask slip, and murders his female victims. He feels no obligation to maintain his male-facing mask with women, signaling their disposability in his eyes. Nude, bloody, and chainsaw-wielding during the film’s climax, Bateman is at his basest, most primal self—closest to the psychopathic, homicidal core inside the constructed character of Patrick Bateman.

We as viewers can likely relate to this. Not that we, too, are secretly homicidal maniacs, but that we recognize in our own nudity that there is not much left to hide, that the pretenses are dropped. In others’ nudity we might also see a truth that had been hidden, or an undeniable, unfiltered connection to our more primitive nature. The artifice of all the trappings becomes clear.

Nudity in American Psycho is vanity, sexuality, and, in a sense, the exertion of dominance. It signals a primal state, a stripping of pretense, for better or for worse… mostly for worse in this case.

A Million Patrick Batemans

In the end, instead of facing justice for his murder spree as we would typically see at the end of a horror film, Bateman faces… nothing. We as viewers are left to wonder whether Bateman really murdered anyone, if it was all in his psychopathic imagination, or if, even worse, because of his status, wealth, good looks, and identity interchangeable with any other high-profile investment banker in the city, nobody really cared. We’re left to wonder if, like powerful men who commit atrocities and subjugate women and behave badly in the real world, he just… gets away with it. And who knows what kind of blood the cast of other interchangeable investment bankers had on their hands. It may not have been the actual blood that Patrick Bateman had on his, but the conversations between these men on screen reveal rampant misogyny, racism, and no real moral code or positive contribution to society to speak of. There are dozens, hundreds, thousands of Patrick Batemans, we might intuit.

The essential horror of American Psycho is not so much the violent murder but its exposure of our unwillingness to hold powerful men accountable for their terrible actions, that we let them get away with it. Yes, Patrick Bateman is a monster, but so is the entire network around him that lets him off, refuses to punish him, even as confesses his sins and begs to be caught. And he’s just one of any number of nearly identical, powerful, untouchable, unstable men. In this way, the film also effectively strips this brand of alpha-male masculinity down to a fragile and primitive pursuit of superiority, vanity, and status, one that is a threat to everyone in its path. It should act as a warning.

The lasting impact of the film, however, is that later generations of young male viewers would not grasp this message and would instead idolize and strive to emulate the vane, woman-hating, self-worshipping, psychopathic, soulless archetype embodied by Patrick Bateman. More horrific than a system where some men get away with murder is a world where men strive to achieve that level of untouchability, inhumanity, and soullessness. More horrific than a dozen or a hundred or a thousand Patrick Batemans is a world full of aspiring psychopaths. No matter how naked and chiseled and perfectly coiffed they are, and no matter their ability to get reservations at Dorsia (or wherever), a million Patrick Batemans is seemingly the enduring horror of American Psycho.

Happy Halloween, readers!

Brilliant! Scary... but brilliant 🙈

There is also The Possession of Joel Delaney. Nudism not in its best light, as the scene involved the forced nudity of a child as away of humiliation, a scene even Stephen King found "out there", but still the young actor did perform the scene as written.